Bob was a radio operator based in Port Etienne 1944-45, with also time spent in Bathurst, Yundum and the Gambia

After the war baptism at the Dover front line casualty hospital, with the ongoing bombing and cross-channel shelling, allied to the constant viewing of the blood and gore of the poor local people alongside early service casualties a la Dunkirk etc., a view was taken that nothing one encountered in war service to ones country, could be any worse – and so it proved to be - and as the story unfolded, ‘Lady Luck’ prevailed.

After the war baptism at the Dover front line casualty hospital, with the ongoing bombing and cross-channel shelling, allied to the constant viewing of the blood and gore of the poor local people alongside early service casualties a la Dunkirk etc., a view was taken that nothing one encountered in war service to ones country, could be any worse – and so it proved to be - and as the story unfolded, ‘Lady Luck’ prevailed.

Calling-up papers to the Army had been received, but as one had already volunteered for duty in the R.A.F., the Army had to be a no-no and documents therefore were returned post haste! Flying duties in the R.A.F. were designated to be training for being a Wireless Operator/Air Gunner.

The big day arrived after a period of deferred service in the midsummer of 1942 – the trek began by travelling from Folkestone to the R.A.F kitting out station at Padgate (near Warrington- first impression a rather dirty and industrial area), the camp being situated someway distant.

So it was then that 1388823 AC2 Lord R.P. was fully enlisted, preparatory to donning the blue uniform. The first night there was pretty hair-raising, billeted in a big hanger, with three layered rickety sleeping bunks - yes yours truly drew the short straw and got the top swaying bunk bed – the night virtually sleepless was like being on the proverbial roller coaster. But survival was the name of the game. Came the dawn, an early start then for the kitting out stakes. Firstly a massive kit bag, into which was somewhat untidily put virtually two of everything; vests, shirts, uniform etc. allied to a massive pair of black boots, forage cap – loads of black buttons, cleaning kit etc etc, the whole caboose weighing half a ton! The rest of that first day spent thus – marking name and number on each article and polishing buttons, boots etc. then the following day the motley crew of about 200 had to go on the parade ground soon after dawn for kit inspection and documentation etc.

Fortunately then the story at Padgate was brief, just two nights in the cold hanger, before kit bag on shoulder, all marched to the local station for en-route to the harsh (!?) training square-bashing regime at reasonably nearby Blackpool, where basic radio operating training was to commence! Along with about a dozen others we were billeted in a civilian house in Albert Rd (not far from the station, sea front), and also fairly near to the famous Blackpool Tower, still the outstanding Lancashire landmark to this day.

Very early each day then, parade in Albert Road, then a quick march to the famous Blackpool sands for a period of intense drill (so called square bashing) under the piercing eye of a ferocious-looking Flight Sergeant who proceeded to bark out words of command that must have been heard miles away – certainly made the attendant company sit up and take notice!

After just about surviving this first vocal onslaught, with the help of a very large jelly cream bun from the Salvation Army van parked nearby allied to a cup of hot ‘char’ (slang for tea- if you could call it that!). Thence onto the first introduction into the world of wireless and morse code at Raiker Parade in the north of town – which I took to very well. So this was to become a fairly daily routine interspersed with rifle drill at the nearby Blackpool football ground ( Stanley Mattthews was a Corporal PTI there – we were able to watch him train – he obviously wasn’t nicknamed the ‘wizard of dribble’ for nothing!)

Six weeks of the foregoing then, but with many pleasant off duty forays into the night life in Blackpool, but with a weekly pay of 10/- (ten bob!) luxuries were limited, however we had out moments, especially taking the local beauty queen home one night from the winter gardens! There was a curfew at 10pm, so this particular sortie resorted travelling back to billet through various side roads and shinning up the proverbial drainpipe at the billet in Albert Rd! Following on from this escapade the big shock came a few days later when after completing the course successfully (top marks in Morse) we did the passing out parade with rifles suitably on the shoulder through the main thoroughfare of the town, on one street corner espied the aforesaid Miss Blackpool – complete with baby in pram and holding another one by hand (not guilty, but stirred and shaken!!)

Then so it was after the conversion of becoming new after being that first day there of a somewhat bedraggled group of youths, but now very fit, the long journey beckoned to No 4 Radio School at Yatesbury in Wiltshire, where we were to learn the intricacies of the internal working of the radio set allied to improving the Morse speed skills. Two short spells of ‘Jankers’ there, one for going A.W.O.L. on Saturday night visiting ones Aunt and Uncle at nearby Thatchem, than another three days for dirty boots. First priority – another tin of cherry blossom metal polish ‘for buttons’, Bull as is was termed being the order of the day- so after this baptism one was really an airman (albeit 2nd class). After a month of ground work the big day arrived, ones first flight in an aircraft; four of us in a two engine Dominie plane, where we had to take it in turns to work the radio with calls back to base at Yatesbury. Our particular destination that day was to Derby, whereby that first sortie could well have been out last as, unknown apparently to our pilot, there was a balloon barrage up over Derby and it meant flying in between the balloon cables – phew! But nevertheless mission accomplished, in spite of feeling somewhat queasy (a feeling to be repeated many times during the course of the flying stakes!). Many training flights followed with a variety of pilots on the small single seater ‘Procter’ aircraft, very often with Poles at the controls, safe in the knowledge that if things went wrong and we had to bail out, he would go first, then ‘Joe Soap’ would follow – imagine (possibly brown trousers!) – sorry!!

After then becoming a survivor of the early intense flying programme, one finally passed the exam, getting first promotion to the exalted position of AC1, with its small increase in pay! Postings then arrived – my luck being to be sent to a station affectionately known as ‘the back of beyond’ to No3 Air Gunnery School at R.A.F. Mona on the Isle of Anglesey. Here the training consisted of air-firing from Ansons at a ‘drogue’ target being towed by another plane around mostly the peak of Snowdonia and the Irish Sea – here virtually all Polish pilots – good pilots, but mad as march hares and many a narrow squeak, especially when I was invited to take the controls of the Anson, with the accompanying plane just under my wing tip. Fortunately we had a recall to base as the mists came down very rapidly around mount Snowdon – so even more dangerous even for experienced pilots – but somehow we survived!

For what reason unknown – whether local conditions and poor food – I developed jaundice, a very debilitating illness, and apparently contagious and notifiable, so straight away departed to an R.A.F. special medical centre at Minster – by train – how I ever got there will never know, feeling by now really ill and weak. However good nursing did the trick (looked after by an ex-windmill fockies girl – that obviously helped!!), but it took a full six weeks before being back on track. Thence after sick leave, to an easy posting to the Radio Signals section at RAF Cosford, near Wolverhampton. Life there being a complete contrast to Anglesey; good food, plenty of entertainment (we had a full fun-fair over the Xmas period on the camp), and met a chum who was to be a chum for the rest of the war and many years after – Ken Webb*.

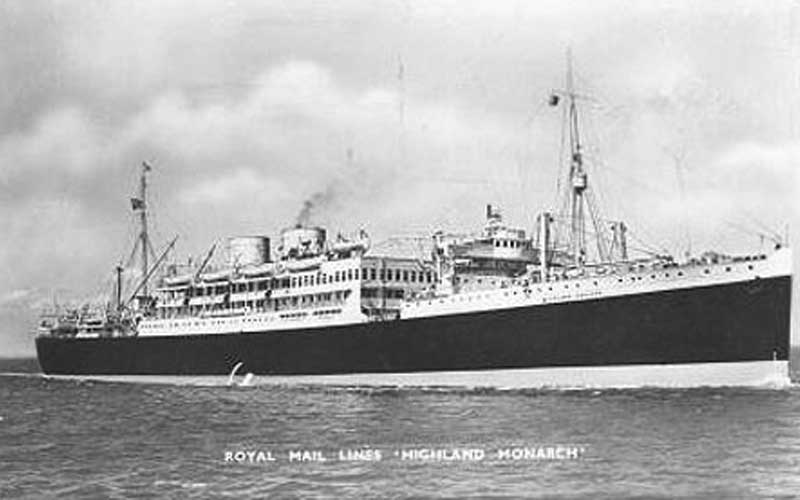

Obviously Cosford was just short time and the day arrived for overseas postings – where? Well a return to Blackpool for tropical kit gave an obvious clue – but unfortunately not flying to whatever destination – so it was off to nearby Liverpool to meet up with the Highland Monarch – a troopship – still unaware of final destination. Very primitive conditions – sleeping in swinging canvas hammocks. After three days there looking at the Liver building opposite to the ship alongside the River Mersey, we were finally to depart into the unknown, but we were soon to find out especially the ‘cruel sea’ of the Atlantic ocean. Boat drill first day out passing between Stranraer Scotland and Larne Northern Ireland sea sickness reared its ugly head well and truly. So some hours on a visit to the ship’s sick bay via a Navy stretcher – to be greeted there by many more casualties – so slight compensation. Leastways the beds there were solid and not rocking- although everything else was with the ongoing heavy ocean rollers, but although shaving was difficult with a weakened frame we survived – in the knowledge that still no news of the final destination.

Obviously Cosford was just short time and the day arrived for overseas postings – where? Well a return to Blackpool for tropical kit gave an obvious clue – but unfortunately not flying to whatever destination – so it was off to nearby Liverpool to meet up with the Highland Monarch – a troopship – still unaware of final destination. Very primitive conditions – sleeping in swinging canvas hammocks. After three days there looking at the Liver building opposite to the ship alongside the River Mersey, we were finally to depart into the unknown, but we were soon to find out especially the ‘cruel sea’ of the Atlantic ocean. Boat drill first day out passing between Stranraer Scotland and Larne Northern Ireland sea sickness reared its ugly head well and truly. So some hours on a visit to the ship’s sick bay via a Navy stretcher – to be greeted there by many more casualties – so slight compensation. Leastways the beds there were solid and not rocking- although everything else was with the ongoing heavy ocean rollers, but although shaving was difficult with a weakened frame we survived – in the knowledge that still no news of the final destination.

Halfway to America then in convoy of some twenty ships with Royal Navy escorts – cruisers, destroyers etc. The welcoming lights of Gibraltar eventually came into view (obviously no blackout in force there!) and the following day to be on deck at 6am to see the sun coming up over the famous rock of Gib, was truly a wonderful sight long to be remembered. A short 24 hour stopover there, then the announcement to all, that our final destination was to be Freetown, West Africa.

To Freetown...

So onwards we travelled still in convoy (available aircraft at a premium) so again with the naval escorting warships. One week on we all at last steam into Freetown Harbour, with temperatures now risen to tropical conditions – which had been increasing since the Canary Islands. The Sunderlands stationed there at Jui came out to meet and greet us. All the young native boys surround our ship in their little canoes, bringing us bananas – the first we had seen for nigh on four years, whilst at the same time diving from their craft into the sea for pennies thrown from the ships side.

Ashore then via the RAF high speed launch – weighed down with kit, but back on terra firma happily once again after nearly three weeks, but on ones knees, with temperatures touching 110º at midday. Thence it was onwards and upwards to RAF transit camp at Hastings (rings a bell!), by train rushing through the main street of Freetown, followed by hundreds of the local youths clamouring for us to throw them English Pennies. They are obviously in a rather poor and under-fed state, so some servicemen handouts are well and truly welcomed!

Week in the transit camp – before the postings came through – which amounted to several other wireless ops and self to be going to RAF Yundum in the Gambia. Still no available aircraft so once again it had to be by ship, but what a ‘hell’ ship it turned out to be – called the Altmark – a very old tub with more ‘livestock’ of the unpleasant variety than men: again in swinging hammocks at night above the mess table – only this time with rats running up and down the guy ropes for company, whilst now the temperatures going through the roof. Fortunately this very slow journey was of short duration for three days onwards to Bathurst – a week there then at last a Sunderland available. It was so good to get on board and meet the crew. However this journey was to be of short duration owing to operational needs, and we came down in the sea offshore at Dakar in French Mauritania. Just three days there, but what a three days! The highlight after leaving the Lysee billet (previously used as a school), we ventured to the red light area to see “L’Exhibition” in a big open aired courtyard, with rooms all round the balcony above. So we paid our 75 francs to view the ‘performance’ of two young ladies – it was really laughable, and only lasted about ten minutes – not exactly the crème de la crème. But that’s as it was – not a lasting memory – but being in French territory, a must see! A couple of beers after this ‘entertainment’ then back to billet.

Onwards to Port-Etienne...

Due to leave Dakar the following day we were hearing that the main parts of town had been put out of bounds – not the “L’Exhibition”, but by bubonic plague – spread like wildfire by the rat population – so we eventually left for out final destination Port Etienne, just in time! So it was that by Dakota aircraft we flew to PE, and our first sight of the Sahara Desert early in 1944, and it was to be the base for the next year. Our signal section there comprised of about six to ten Nissen huts allied to the Sunderland base on the water, just a mile down from the camp. Surprise, surprise maybe, but I look back on my stay in the desert with many positive and good memories. The start was somewhat grim, having to make a water bottle last for drinking and washing purposes for the first three days, allied to sleeping on a hard concrete floor, but conditions soon settled down, with supplies aplenty arriving via the supply ship offshore.

Life at Port-Etienne certainly was never dull, and many retentive good, bad happenings whilst there, but mostly fortunately the former. On the positive side our operating side gave us plenty of opportunity for free time whilst at the same time the Sunderland patrols were covering mainly adequately the sea-lanes down the coast looking out for the German U-boats (submarines). Six of our aircraft had been blown over in the bay of Bathurst, and had to go out of service for repairs – caused by a sudden whirlwind. A land plane had to make an emergency landing on our sand runway with explosives on board, whilst one night we had to talk down a Sunderland at night caught in a serious sand storm over us; mission was accomplished but the crew were very shaken when coming ashore as it had been a close call and fuel had been running low. The major happening however was that the land mail plane en-route to us with six weeks mail onboard crashed north of us at Rabat, and sadly all the crew perished.

On the brighter side a good swim in the warm sea daily helped with the health stakes – and the freedom from uniform was wonderful, invariably just wearing a something of khaki shorts each day, and all by now looking as brown as berries! Our dhobi boys were all Arabs and slow but in the main good workers – they would do anything for English cigarettes which were fairly plentiful for us. Heard news after leaving that my special lad nicknamed ‘Dopy’ had been electrocuted there at sixteen years of age – quite sad news for all on hearing this en route later for home. We shared the camp with part French naval forces and Sudanese Foreign Legion bods who had their own ‘fort’ nearby.

Drink of an alcoholic nature was cheap – with the French martini being popular – ten pence a mugfull (10D!!). but we limited ourselves to having one big party at Christmas there 1944, it lasted nearly a week. No problems as such, with everyone enjoying themselves and having a good time, with camel races. Fancy dress fun and putting on a stage concert show with the signals officers dressing up as females – a real something.

Two strange happening whilst at P.E. We had a big plague of locusts descend on us one day, obviously blown over by a big wind change from the east. We used the flit sprays to get rid of them in our billet by lighting the fuel and using it as a flame thrower, they all disappeared within an hour. The other oddity was when it suddenly rained one morning for a whole minute! Everybody dashed outside in their birthday suits to feel, albeit briefly, the cooling water. It was reported to be the first rain there for the previous ten years!

The only major health problem was that invariably most of the crews went down with the dreaded dysentery at some time or another, which was very debilitating. It resulted in crossing the sand many times at night to the wooden loo (just a bucket) with but a candle for light. Quite an experience with invariably quite a queue of bods vying for one of the primitive six compartments.

A Sunday highlight was being asked by the padre to read the lesson in our Nissen hut church in front of the whole unit and being congratulated afterwards by him, quite a pleasing and uplifting experience. Time came then, early in 1945, to set off for home again (affectionately known as Blighty). So the Dakota aircraft duly arrived and took six of us back to Freetown, where owing still to aircraft shortages we once again boarded a trropship and set sail for good old Britain. This journey being although a relief, was not without incident. U-Boat packs were still operating and one of my many tasks was to sit on guard during the night manning a Lewis, or was it a Bren, Gun in the focsle (high up on the side of the ship). There were no incidents, although it was reported that there was a U-Boat pack still operating in the Mersey Bay area and we did hear the distant sound of exploding depth charges. But as far as I’m aware all the ships ion our convoy arrived back to Liverpool safely.

A weeks stay there in a private billet at nearby Morcambe for disposing of tropical kit etc. Then homewards back to Folkestone, awaiting news of new UK posting. It was shortly to come, the war was nearing its end, flying crews were reduced in numbers, and the spot they chose for me was Chicksands Priory in Bedfordshire to join the Y-Service, a radio monitoring side to the famous Enigma decoding service at Bletchly Park.

It was May 8th 1945, one of the most memorable days of my life and for countless thousands of others, VE Day!!!

Although the camp itself was in fete, I was given a three-week leave pass (disembarkation leave) and straight away headed back to London. What a wonderful city it turned out to be that particular day, everybody but everybody in jovial mood and extremely happy that the war had finally ended. All of us service folk were given a wonderful reception by the waiting civilian bods lined alongside the pavements. I found myself joined by an American Colonel on one arm and a Petty Officer on the other. So we joined our long lines of celebration going onwards from Piccadilly through to Leicester Square and onwards with Scottish pipers leading the way. A real jolly hullabaloo with the Londoners thrusting drinks into our hands and all singing the by now famous wartime songs; “we’re going to hang out the washing on the Seigfried Line” and “we’ll meet again” by Vera Lynn, etc The razzmatazz went on for hours, culminating in a march down to Buckingham Palace to see the royalty on the balcony there, and above all, our great man Winston Churchill, giving to all of us his great V for victory sign!

The night was spent sleeping alongside a group of Ghurkha soldiers (another great bunch), then the following day back to Folkestone wearily for a well-earned rest and leave!

So I was then to spend a year at Chicksands before final demob. It was in the main a good twelve months. I organised a billet football team, and mixed hockey eleven playing local sides, sometimes two in one day! The work involved monitoring German radio, and later the Japanese (this was still going on until the atom bomb on Hiroshima). It was quite an experience to be put in charge of a watch of 24 WAAFs, some who had been abroad but the majority having been home based. There were lots of night shifts, I was once asked by the visiting duty officer to put one of the WAAFs on a charge for falling asleep on duty. On telling her there were floods of tears, so needless to say scrubbed round it, soft hearted that’s me! (Or was there a date in the offing?).

There were many demob parties for all held regularly at nearby Luton. Then the big day arrived for ones own departure from Her Majesty’s Forces, so it was finally to departure centre at Uxbridge for civilian clothing and documentation etc. Plus of course a closing payment account, and the discharge book to be signed by the CO.

The Commanding Officers remarks in my discharge book were very flattering, and much appreciated:

“This NCO has performed his duties in a very satisfactory manner. He has a very good sense of responsibility, and is trustworthy” – Signed, Squadron Leader Stevenson.

With my departure date being 6th September 1946, and final date of release 13th November 1946.

Although this was ones end in the service life, it wasn’t over quite yet as, with the many friendships formed over the preceding four years, reunions were quickly formulated during our lives again as civilians, but with the ‘service’ angle very much in mind.

So it was then that with many Anglo-Scottish friendships formed in West-Africa with ongoing contact via telephone and correspondence, the arrangement for our first reunion was duly made. The idea was that we would in the first instance meet in Edinburgh Scotland for the Scotland v England First International after the cessation of hostilities in the ‘other’ war going on against the Japanese. This happened with the dropping of the atom bomb by the Americans on Hiroshima in August 1945. Where after the Japs immediately sued for peace – granted.

Plans were made then for our Scottish visit and tickets obtained for the Hampden match. So together with my special chum Ron Graham (Sheerness), we duly set off to be met at the Waverly Steps, Edinburgh, to be met by the Scottish Bods; John Burns, Alec Ferguson etc etc, twelve of us in all!

What a wonderful few days we were all to have, firstly to our accommodation at the 4-Star hotel, “The North British” in Princess Street in the heart of the city. It was a great place, good meals, a lovely bar and friendly staff.

Our routine from the Thursday to the Saturday for the big match was for all of us to meet up at 10AM to go to the Scots lads special club, and enjoy their special brew; bottles of ‘Prestonpans’ beer, or their ‘weeheavies’ as they called it. It certainly packed a punch, so the afternoons were invariably spent in the big Edinburgh Zoo watching the wonderful array of animals feeding and then dozing, and we followed suit.

The big match on the Saturday was an experience; 140,000 packed into Hampden Park. But the twelve of us all had tickets, and a spare because one couldn’t make it. A tout or customer in the local pub offered us £10 for it (a 7/b ticket!). But being good Englishmen we only accepted face value. The game was good, the result something (I think we won!). And so then to our last day, the Sunday, no hostelries allowed to open in the city that day, but our hosts took us to Gramond Bridge. Three miles from the city centre, where a nice hotel on the edge of the Forth was open all day. After suitable refreshment we took the Forth River, an experience as we went under the magnificent Firth of Forth bridge, towering miles seemingly above us, with railway trains going along the top (as featured in the film ‘The 39 steps’). So the following day it was goodbye to our friends and looking forward to the following year when it would be our turn to do the honours.

And so it came to pass. In 1948 we all met up again in the home stakes of London for the match at Wembley. I believe all stayed at the Strand Palace Hotel, just having two days there. But this was enough to take in the sights, and hopefully to reciprocate something of the delights we English had the previous year in Scotland.

Sadly with marriages in the offing (my own was in 1949), and various movements and addresses there were to be no more reunions. But I did manage to get the Scottish something and a special friend down to Folkestone to stay with us with his girlfriend for a short while. He was John Burns who worked in the Sheriff’s Office in Edinburgh and had been with me for a long time in Furham in West Africa, a good lad and fun to have around.

So this then, is virtually then end of the wartime service story, an adventure in my life I wouldn’t have missed for worlds. The friendships formed, seeing different areas of the world (over twenty RAF stations in all), and above all the discipline; turning virtual boys into ‘real men’, starting at the onset with the Sergeant Major touch of barking commands ‘jump to it’ and ‘turn out smartly’, something unfortunately not so prominent in the lives of the young these days. Ah well, happy days!!

Per Ardua Ad Astra

Addendum

Just prior to the overseas posting – sent to a hanger at Chigwell in Essex and put on reserve for “D-Day” landings in France – hundreds there – but services not required, hence return to Blackpool for overseas posting. Two ‘bods’ on that reserve list – apparently got sent to France on that special day June 6th 1944, and I believe they were both killed - Tommy Kibble and Harry Taylor, both personal friends, very sad. But then ‘war’ was just the luck of the draw – especially survival – otherwise this epistle would never have been written – serious food for thought – why me?